- How would YOU interpret her initial ECG shown in Figure-1?

- What do you think is the cause of her symptoms?

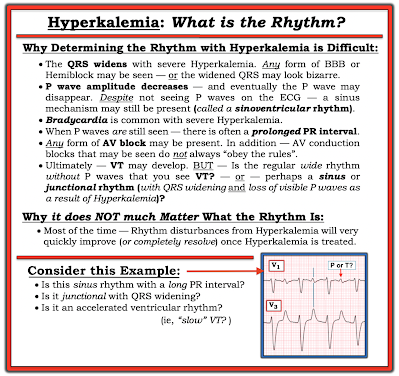

-USE.png) |

| Figure-1: The initial ECG in today's case. (To improve visualization — I've digitized the original ECG using PMcardio). |

- On her 2nd-ED-Visit — She presented after syncope and a fall. She reported several episodes of "dizziness" in the days prior to this 2nd ED visit.

- Her exam in the ED was "normal".

- Her repeat 12-lead ECG was virtually identical to that seen in Figure-1.

- Basic lab was unremarkable.

- The patient was discharged home.

- On her 3rd-ED-Visit — She presented to the ED with a presyncopal episode and ongoing dizziness.

- Her initial exam was unremarkable.

- Her repeat 12-lead ECG was once again unchanged from that seen in Figure-1.

- Basic lab was again unremarkable.

- The patient was placed on a monitor for a period of observation in the ED. Suddenly — the patient became unresponsive! The rhythm strip shown in Figure-2 was recorded.

- How would you interpret the rhythm in Figure 2?

- What diagnosis is suggested by the history in today's case — given the 2 tracings shown in Figures-1 and -2?

- It looks like very low amplitude but almost regular P waves are seen throughout the tracing

- The rhythm is sinus at ~80-85/minute.

- The PR interval is at the upper limit of normal ( = 0.21 second).

- The QRS is wide (3 little boxes in duration = 0.12 second).

- QRS morphology in the chest leads is consistent with RBBB conduction (ie, predominant R wave in right-sided lead V1 — with a wide terminal S wave in lead V6).

- QRS morphology in the limb leads is consistent with LBBB conduction (ie, all upright QRS in left-sided leads I and aVL). In addition — there is marked LAD (Left Axis Deviation).

-labeled-USE.png) |

| Figure-3: I've labeled today's initial ECG. |

- An ECG pattern consistent with RBBB in the chest leads (ie, with a widened, predominantly positive QRS in lead V1).

- An ECG pattern consistent with LBBB in the limb leads (ie, with a widened, monophasic QRS in leads I and aVL).

- NOTE: Variations on this above "theme" of MBBB are common. Thus, the S wave that is typically associated with RBBB patterns in lateral chest leads V5,V6 may or may not be present. In the limb leads, rather than a strict LBBB pattern — more of an extreme LAHB (Left Anterior HemiBlock) pattern will often be seen (ie, with wide and predominantly [if not totally] negative QRS complexes in the inferior leads — and with a smaller [blunted] terminal s wave in leads I and aVL).

- BOTTOM Line: Knowing the clinical history may aid in recognition of IVCD patterns that are consistent with MBBB (ie, if the patient has a known history of severe, underlying heart disease). Distinction from simple bifascicular block (ie, with RBBB/LAHB) — may be facilitated by seeing one or more of the following: i) More of a monomorphic upright QRS in lead V1 (which lacks the neatly defined, triphasic rsR' with taller right "rabbit ear" seen with typical RBBB); ii) Lack of a wide terminal S wave in lateral chest lead V6; iii) Seeing an all-positive (or at least predominantly positive) widened QRS in leads I and/or aVL, with no more than a tiny, narrow s wave in these leads; and/or, iv) Seeing widened, all-negative (or almost all-negative) QRS complexes in the inferior leads.

- Given the history — one might not have chosen to insert a permanent pacemaker after this patient's 1st ED visit. However, the diagnosis of MBBB should be recognized from this initial ECG shown above in Figure-1 because the rhythm is sinus — the QRS is wide — and as shown in Figure-2, QRS morphology "looks" like RBBB conduction in the chest leads, but LBBB conduction with left axis in the limb leads.

- IF one recognizes MBBB on this 1st ED visit — and then considers the feeling this patient had on awakening "that she was going to die" — the astute clinician could have suspected that the patient may have had a bradyarrhythmic form of AV block, and therefore continued to monitor the patient in the ED (and depending on the history — potentially admitted the patient to the hospital for an additional 24 hours to monitor her rhythm).

- And, even if nothing showed on those additional 24 hours of telemetry, given the diagnosis of MBBB — the patient should have been warned to promptly report any "dizzy episodes". Especially given several subsequent "dizzy episodes" over the next few weeks, had this been done — the patient could have been diagnosed and paced long before her 3rd ED visit.

- PEARL #2: As per the famous aphorism by Sir William Osler, "Listen to your patient; He/she is telling you the diagnosis". All too often the diagnosis is there being told to us by our patient, if we only allow ourselves to listen (ie, Today's patient telling us she was awakened with the feeling she was "about to die" — and then had more episodes of "dizziness" in the days prior to her 2nd ED visit).

- PEARL #3: The entity of MBBB is often cited in the literature as being "rare". That said, since I've become aware of this entity — in my experience, it is not rare. Instead, I find this situation similar to what I've experienced with certain specific ECG patterns, such as a Brugada-1 ECG, Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy — and blocked PACs. Each of these entities once seemed "rare" to me — until I became aware of them. And now that I've become experienced in recognizing Brugada-1 ECGs, Takotsubo CM, and blocked PACs — they are no longer "rare", but deceptively common under the right clinical circumstances (See ECG Blog #394 and Blog #419 for 2 more examples of MBBB).

- Many textbooks describe QRS widening as being defined by a QRS ≥0.12 second in duration. But is this truly the best defining limit for QRS widening when there are cases of fascicular VT in which QRS duration is less than 0.12 second? (Kapa et al — Circ: Arrhythm and Electrophys 10(1), 2017).

- The definition of QRS widening is different in children. The reason for this is simple: It takes less time to depolarize a smaller heart. Therefore, QRS duration should normally be ≤0.10 second in children up to ~12 years of age (Rijnbeek et al — Eur Heart J 22:702-711, 2001 — See Table-2 in this reference).

- PEARL #4: For practical purposes — I find the easiest way to define the QRS as being "wide" in an adult is — IF the QRS complex in any lead is clearly more than half a large box in duration (ie, Since each large box on ECG grid paper = 0.20 second — more than half a large box = ≥0.11 second).

- PEARL #5: More than simply determining if QRS duration is ≥0.11 second — the reason to focus our attention on whether or not the QRS is "wide", is that we are trying to exclude the possibility of a ventricular rhythm.

- Be aware that one or more leads in our assessment may look deceptively narrow if the initial or terminal part of the QRS lies on the baseline in the lead being looked at (which is why, "12 leads are Better than One" ).

- It is for this reason that: i) I always look extra carefully when measuring QRS duration if a number of QRS complexes seem like they may be wider-than-they-should-be; — ii) We need to look carefully at all 12 leads at the onset and offset of the QRS when measuring (I find this easiest to do by selecting QRS complexes that either begin or end on an ECG grid line); — and, iii) We should choose as our QRS duration measurement the longest complex for which we can accurately determine the onset and offset of that QRS.

- Today's patient has MBBB. This woman was extremely symptomatic at the time she presented to the ED with recurrent syncopal episodes. Eventually (ie, on her 3rd ED visit) — she experienced an extended episode of profound bradycardia consistent with PAVB (Paroxysmal Atrio-Ventricular Block) — as discussed in the ADDENDUM below.

- The patient was referred for permanent pacing.

==================================

Acknowledgment: My appreciation to Ahmed Marai (from Irak) and Amr Elhelaly (from the UK) — for allowing me to use this case and these tracings.

==================================

- ECG Blog #205 — Reviews my Systematic Approach to 12-lead ECG Interpretation.

- ECG Blog #282 — reviews a user-friendly approach to the ECG diagnosis of the Bundle Branch Blocks (RBBB, LBBB and IVCD).

- ECG Blog #203 — reviews ECG diagnosis of Axis, Hemiblocks and Bifascicular Blocks.

- ECG Blog #394 and ECG Blog #419 — for 2 more examples of MBBB.

ADDENDUM (This Addendum is reproduced from ECG Blog #419):

- The patient's history of a number of episodes that presumably were short-lived with spontaneous recovery — is consistent with PD-PAVB.

- PAVB is characterized by the sudden, unexpected onset of complete AV block with delayed ventricular escape — therefore resulting in a prolonged period without any QRS on ECG. Prior to the prolonged pause — the patient manifests 1:1 AV conduction without other evidence of AV block (which is why onset of PAVB is typically so unsuspected! ).

- Because of its totally unexpected onset and propensity to result in sudden death — PAVB is difficult to document and significantly underdiagnosed.

- Three mechanisms for producing PAVB have been described: i) Vagally mediated (ie, Vagotonic Block — as described in ECG Blog #61, with the references listed at the end that Blog post citing instances of transient asystole from excessive vagal tone!); — ii) Intrinsic (Phase 4 = pause- or bradycardic-dependent) PAVB; — and, iii) Idiopathic.

- The problem with vagotonic PAVB is localized to within the AV Node.

- There will often be a "prodome" of diaphoresis, nausea, dizziness — with the patient aware of imminent fainting.

- Characteristic ECG findings of vagotonic PAVB include progressive sinus rate slowing — often associated with an increasing PR interval and a narrow-QRS escape focus — followed by recovery with progressive return to a normal sinus rate and normal PR interval.

- PD-PAVB is the most likely mechanism for the cardiac rhythm in Figure-2 from today's case. The underlying pathology is severe His-Purkinje System disease (strongly suggested by the presence of MBBB in Figure-3 of today's case). This form of PD-PAVB is likely to be fatal unless the patient receives a permanent pacemaker.

- The interesting pathophysiology of PD-PAVB results from chance occurrence of an "appropriately-timed" PAC or PVC that partially depolarizes the diseased HPS (His-Purkinje System) at a specific point in the cycle that renders the poorly-functioning HPS unable to complete depolarization. The resultant prolonged pause in ventricular depolarization may only resolve if another "appropriately-timed" PAC or PVC occurs at the precise point needed to "reset" the HPS depolarization cycle (which presumably explains why the patient in today's case spontaneously recovered).

- Of note — although severe underlying HPS disease is evident from the bradyarrhythmia seen in Figure-2 of today's case — up to 1/3 of patients with PD-PAVB do not show evidence of conduction defects on ECG, thereby complicating documentation of this diagnosis.

- The baseline ECG before idiopathic PAVB tends to be normal.

- No "trigger" for PAVB is evident (ie, no source of excessive vagal tone — and no precipitating PACs/PVCs are seen).

-USE.png)

-USE.png)

-USE.png)

-labeled-P-USE.png)

-labeled-maybe-USE.png)

-ECG_Guru-USE.png)

-USE.png)

-labeled-USE.png)

-USE.png)

-USE.png)